At the University of Miami, my teaching fell into two broad categories. As Librarian for the Cuban Heritage Collection and Religious Studies and Curator of Latin American Collections I instructed students from a variety of departments in how to research and use the resources available through the library, both in person and virtually. Searching for materials and conducting research require guidance and practice to do well, and every student can learn something that will enhance their academic and future careers immeasurably.

I led sessions for students to work with our collections, be they archival materials such as letters, photographs, maps, and diaries or secondary sources, including published books, newspapers, and journals. There is nothing like holding and examining a fifteenth-century book and seeing the traces of previous owners in the margins and the creases of the pages. More and more materials are also available digitally, either scanned from original copies or “born digital,” an example of the latter being those photographs you took on your phone and uploaded to Instagram. Posts, books, blogs, journals, newspapers, magazines and so much more is available at our fingertips – our digits – that people like me and many others help navigate the quagmire of information to find reliable, beautiful gems that can be used and cited with pride in original and fresh work. These library-based sessions are often one or more sessions of a class that regularly meets on campus, say for “Caribbean History” or “Africa in Cuba, Cuba in Africa,” and the professor will reach out and request to bring the class in and build classes around our exceptional holdings.

Instructor of Record Teaching and the Unessay

Another aspect of my teaching life is being an instructor of record. I hold a secondary Assistant Professor teaching appointment in the Department of Anthropology, and I have also taught classes for the Department of Religious Studies and Latin American Studies. I particularly enjoy teaching the Anthropology of Religion. I have been asked to teach Caribbean Religions. In my Latin American and Caribbean Studies class, I crafted the syllabus to introduce students to the region and express their creativity through the final assessment piece, an “unessay.”

The unessay concept was inspired by the primary sources I use in my library-related teaching and the focus and theme I developed throughout the Latin American and Caribbean Studies class. Introductory courses in this field are notoriously difficult to organize since they cover multiple disciplines and [should] involve the cultures and histories of 44+ countries and multiple languages. I devised a way to incorporate extensive use of primary documents throughout the semester. I combined this with a “meta-frame” for the course, asserting and discussing that relationships of power create paper (with “paper” is broadly defined to include art and realia). Primary sources illustrated aspects of culture and history and interrogated their power. As a class, we discussed the many ways that power and paper surfaced in our everyday lives: marriages and divorces are signaled by paper; letters home; stamps used to get them home; the diplomas these young minds had their sights set on; parking tickets; bonds – both of the jail kind and the Wall Street kind; paper money; contracts for things and not too long ago people; and so on and so on. Moving beyond a “show and tell” formula of class use of library materials, the students worked with ideas about power and relationships. They discussed how these manifested physically in the objects and materials on specific topics that spoke to them.

My students were charged with creating or authoring an object or product called an unessay in any form they wanted. I adapted this assignment from work by a Rare Book School Fellow and mentor, Dr. Ryan Cordell, and scholar, Dr. Daniel Paul O’Donnell. The objective is to give poetic license to see what can be gleaned when the student can work in any way they wish (i.e. make a game, a podcast, a film, a book, poetry, a sculpture, a song, a poster, etc.,). The caveat for grading is that their chosen medium has to effectively and unequivocally express their intended message. The student can bring their unique talents and creativity to the class and demonstrate and apply it to learning about Latin America, the Caribbean and interpret or explore our ongoing discussion about the interplay of “power” and “paper”. Throughout each class and especially each visit to examine a wealth of primary sources at the library and the Lowe Art Museum, I impressed my students that they could take inspiration from the materials we examined and discussed for their unessay final project. Students had a long lead time to create their unessay and were free to consult with me and others as often as they wished. Oh, students were also given the option of an essay question. Only two students out of nineteen opted to take those routes.

At the culmination of the semester, students demonstrated their unessays in class (they also handed in a written reflection of the process and the project along with the unessay). To say this was one of the most encouraging and satisfying moments in my teaching career to date was an understatement. Each student was energized by the primary sources they had seen in class, and their unessays were stellar. I wish you could have witnessed the energy and the excitement with which each student introduced their project. Students took great pride in showing their work – they seemed much less nervous than in a standard class presentation, and students eagerly asked questions about each other’s work, took pictures of work of interest, and were invited to share links to digital work. None of this creativity, sharing with excitement, or interaction would have happened if they had simply turned in an essay or focused only on secondary source readings.

Below are just a few examples of my students’ unessays

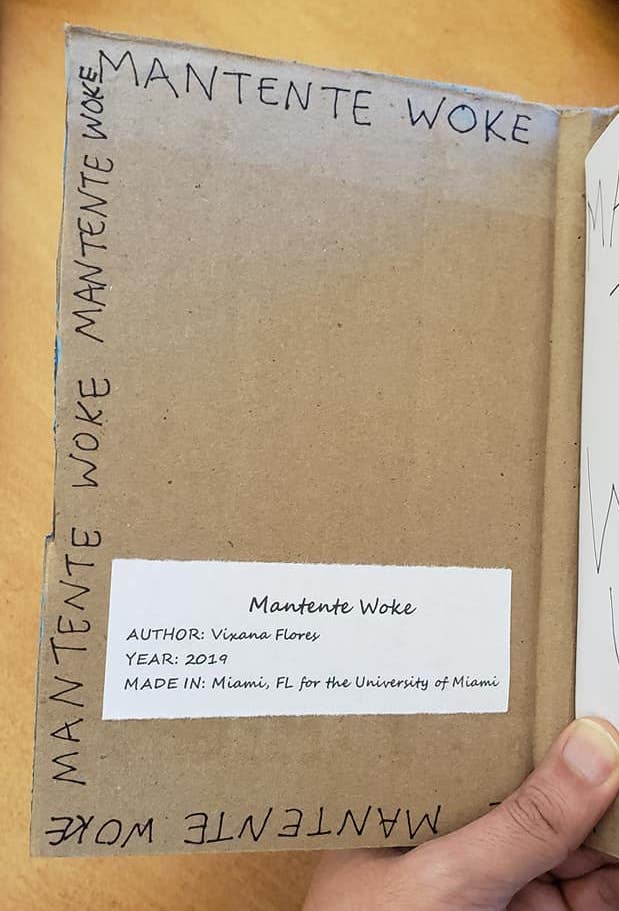

Two students made cartoneras after examining them together during a class during our semester. Cartonera is a social, political, and artistic publishing movement that began in Argentina in 2003 and has since spread to countries throughout Latin America and, more recently, to Europe and Africa. Cartonera books are handmade in cooperatives, often by women, from cardboard bought from street vendors at three to five times the price set by recycling plants. The books express the interests and concerns in the streets that explore injustices, political and socio-cultural themes. They have become “artivism” pieces collected globally and used for teaching in many institutions. One of our classes was devoted to exploring this genre. One was a bi-lingual cartonera about activism in Argentina entitled “Mantente Woke” (Stay Woke). A second cartonera dealt with the culture, customs and food of Peru.

Another student was moved by primary newspaper accounts of the deaths of trans-sexual community members in Brazil. She compiled a spreadsheet of specifics of each of the 331 murdered trans persons. Then she created an elaborate, multi-layered box that looks like a present or jewel box but, when opened, reveals a monument to their lives and the circumstances of their deaths. Thus, a different primary (paper) source considered multiple actors and showed the victims’ humanity in a new and powerful light.

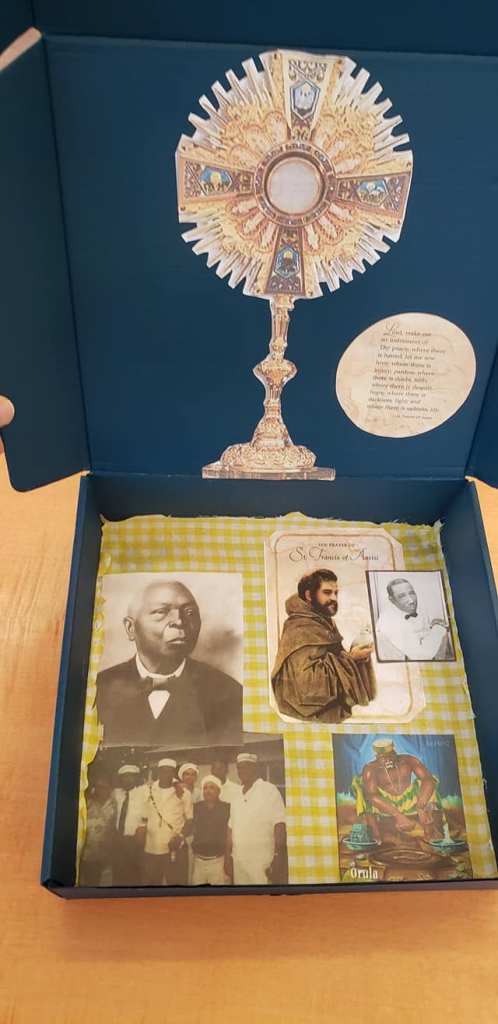

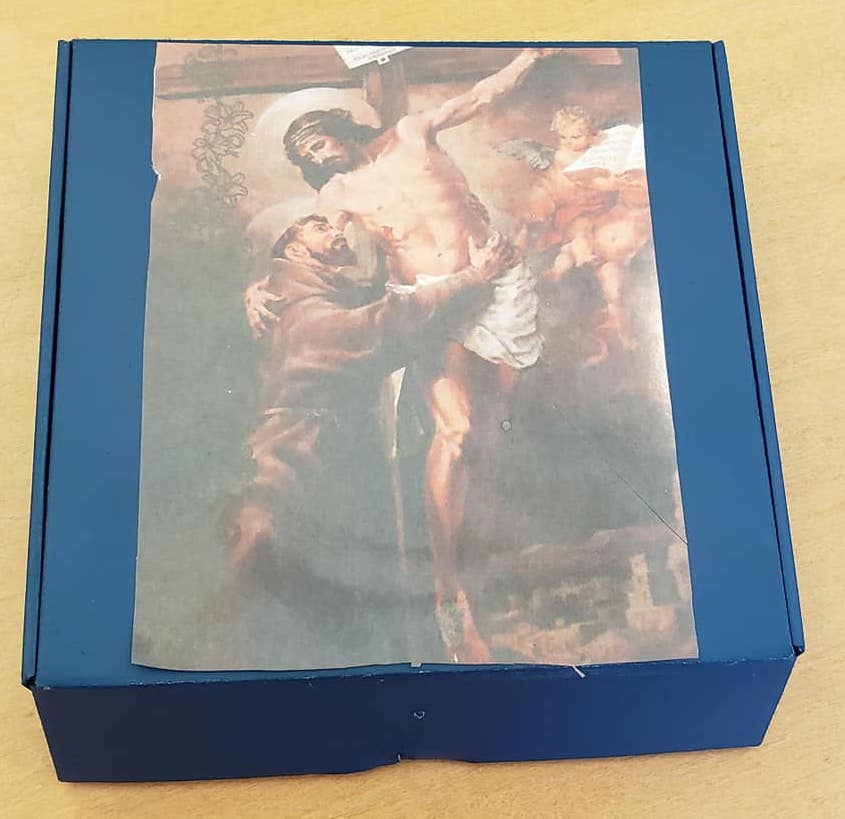

A fourth student from a family that practices Afro-Cuban religions and whose father and grandfather are babalawos (divination priests) created a box of destiny featuring images associated with Ifá divination. On the box, he placed odu or divinatory verses that are symbolized and maneuvered through binary markings and placed photographs of important Afro-Cuban babalawo ancestors as well as Catholic imagery that has played a pivotal mnemonic role in veiling the religion when necessary. He created an opele or Ifá divining chain made of dried fruit and beads after he read primary sources revealing that the first such divination instruments used by babalawo in Cuba were made from dried orange peel segments.

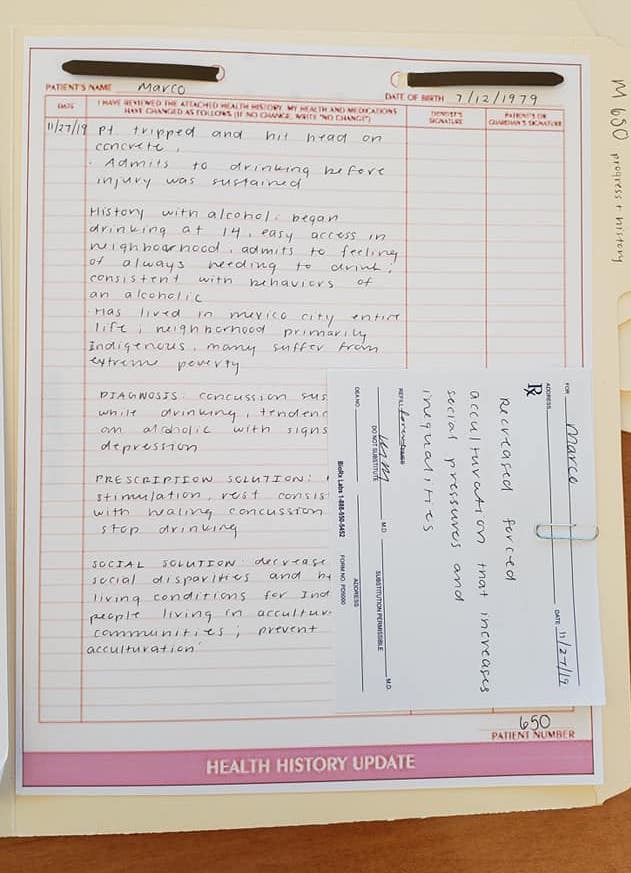

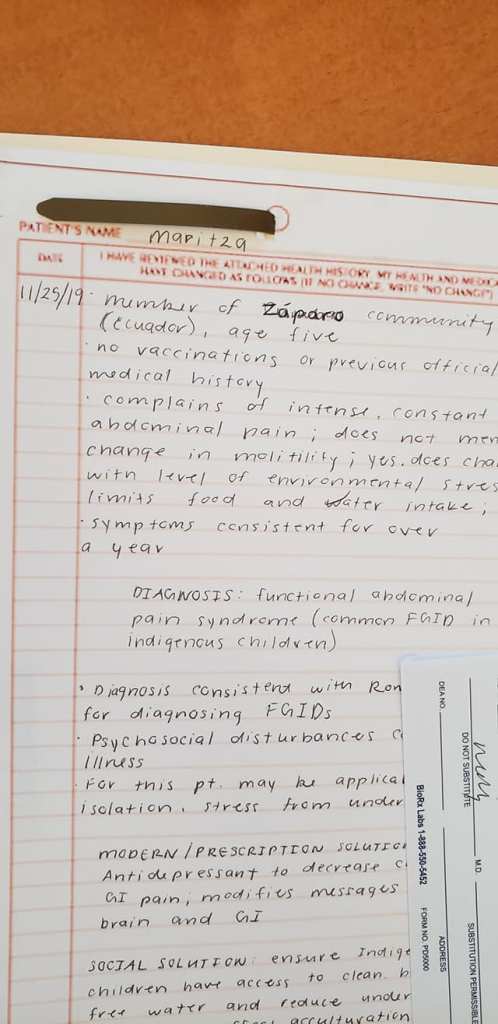

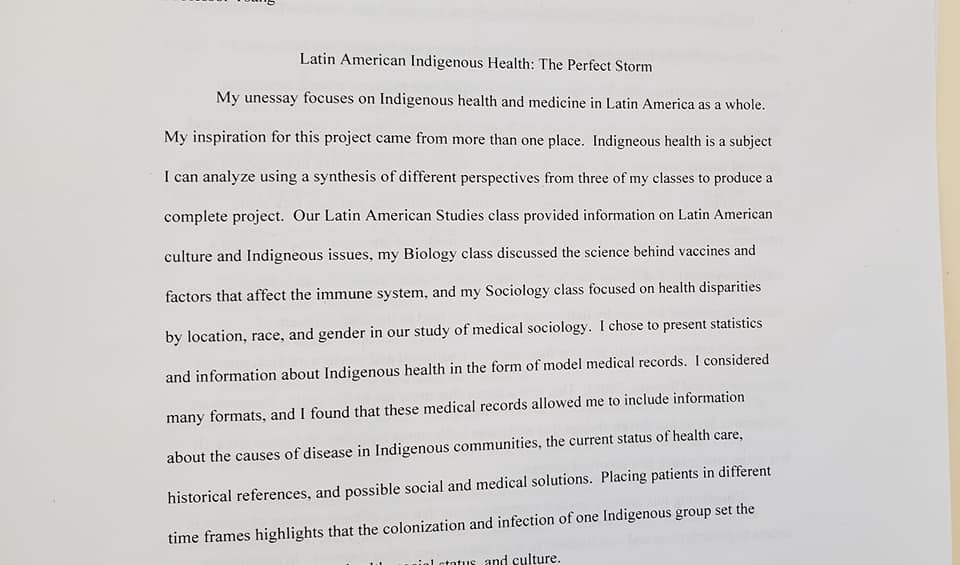

This student created paper medical records for four indigenous Latin American patients as if being treated by Western medicine, noting disparities of care and legacies of colonialism. She explored a colonial disease – smallpox in one patient and commented on infant mortality rates in another. Each file was complete with medical check-ups, diagnoses, and prescriptions. The files were accompanied by a précis and analysis of the overall project.